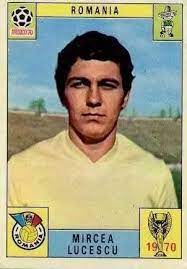

Mircea Lucescu is arguably the titan of post-war Romanian football. As a successful player, as an even more successful manager, and in his current incarnation as a polyglot, generally benign uncle-figure who takes care of his boys during wartime and still wins trophies, ‘Nea Mircea’ is celebrated both at home and abroad like few other Romanian figures. He was born in Bucharest in July 1945, not long after the end of the war. He made his international debut in 1966, the year after Ceausescu succeeded to the leadership of the country. (At the time he was a second division player, on loan from Dinamo to Stiinta Bucuresti.) The national team captaincy fell to him in January 1969, shortly after Ceausescu had denounced the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. As coach, he would sweep the first post-Ceausescu domestic trophies in 1990. But first, this.

Lucescu was appointed Romania coach as a temporary measure in late 1981, after Valentin Stănescu had failed to get the team to the 1982 World Cup finals in Spain. After a bright start, with a win and a draw against England, under Stănescu the campaign had fizzled out with home defeat to Switzerland. Hungary and England qualified ahead of them. In the eight games, Romania had scored just five times.

Lucescu was a man intimately familiar with the international game and with the cream of the nation’s playing talent. He had won a then record 70 caps for Romania, making his final appearance in 1979 in a European Championship qualifier against Spain. Just two and a half years later, aged 36 and only just retired from playing altogether, he was busy guiding unfashionable Corvinul Hunedoara to their best-ever performances (they would finish third that season), when he was invited to take the reins of the national team.

Difficult days: Romania in 1981

When Lucescu took charge as Romania coach in 1981, Bucharest had just hosted the country’s biggest ever sporting event, the World Student Games or Universiade, attended by several thousand athletes from across the globe. The country’s most famous person, Olympic champion gymnast Nadia Comaneci, made her first major home competitive appearance on that stage, in what also turned out to be her last (while still only 19). The venue for this high-profile extravaganza was the Regie complex, the home of the very Stiinta club where Mircea had cut his teeth as a player. The celebration of youth and sporting excellence was scarcely marred by the falsification of a couple of competitors ages to make them old enough to qualify, or by the rounding up of thousands of dissidents into a mental hospital for the duration.

Bothered by external criticism of his regime, Ceausescu appears to have sponsored the bombing of Radio Free Europe’s Munich headquarters in February, and in July the Securitate attempted to assassinate RFE’s high-profile Romanian journalist Emil Georgescu, a thorn in Comrade Nicolae’s side. Chief of the Romanian section, Noel Bernard, died in December of an aggressive cancer (poisoning was suspected).

1981 was also the year Ceausescu took a monumental economic decision, which had ramifications throughout the rest of his rule and beyond. He resolved that Romania would repay its foreign debt as soon as possible, an unorthodox policy which entailed swingeing austerity measures. Focus on exports resulted in energy rationing and severe food shortages at home. Unfortunately, in Ploiesti crude oil was drying up; in the Jiu Valley coal miners went on strike. School children and university students were conscripted into the agricultural labour force at harvest time, belatedly replacing the men who had moved into towns to take the new jobs created by the rapid industrialisation of the ’60s and ’70s. The rationing of basic foodstuffs such as bread, milk and oil was implemented outside the capital. In response to shortages of meat and eggs, the government declared that Romanians ate too much meat anyway.

Eyes were on Poland, where broadly similar economic mismanagement gave rise to the Solidarity movement in 1980. Spreading unrest would soon lead to the imposition of martial law by the beleaguered government in Warsaw. Ceausescu was determined not to allow Romania down the same path.

The dictator was rolling out his grand plan – inspired by a visit to Pyongyang and expedited by the earthquake of 1977 – to demolish a sizeable part of the old centre of Bucharest and replace it with a modern ‘civic centre’. A competition was begun in 1980 to design the centrepiece, the Palace of the People, a monstrosity of a passion project which would, famously, remain incomplete at the time of Ceausescu’s overthrow.

Young boys in Switzerland: Bern, 11.11.1981

Back to the football. Lucescu’s first game in charge of the national side was the final World Cup qualifier, the dead rubber return fixture against Switzerland in Bern. Nudging aside some of the regulars, he handed international debuts to a bunch of trusted Corvinul players.

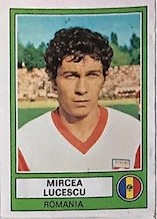

Midfield stalwart Anghel Iordănescu had played his last international. His Steaua team-mate, centre-half Ştefan Sameş, and Dinamo’s Dudu Georgescu – who is to this day the Romanian top division’s all-time record goalscorer – would each play only one more competitive international. The trio were hardly over the hill, all 31 years old, with over 150 caps and 40 goals between them, but clearly this was a time for sweeping change and they joined former skipper Cornel Dinu (age 33, with 75 caps) on the scrap heap. The international careers of regular first-choices Zoltan Crișan and Ion Munteanu were also all but over. Meanwhile, Romanian Footballer of the Year 1980, tricky midfielder Marcel Răducanu, had effectively ruled himself out by defecting to West Germany after a friendly match against Borussia Dortmund in August.

So only three players remained in the starting line-up from the previous match, and they were all from Universitatea Craiova: midfielder Aurel Ţicleanu (22), centre-half and captain Costică Ştefănescu (30), and Ilie Balaci (25), the creative fulcrum of the team.

In came a Corvinul pair, defender Mircea Rednic (19) and the versatile Michael Klein (22), alongside Sportul Studențesc’s Gino Iorgulescu (25) and Dinamo’s full-back Nelu Stanescu (24), all for their first international starts. Another debutant, Corvinul’s Romulus Gabor (20), started up front, next to Sportul’s experienced Mircea Sandu (29), who was making his first competitive start for six years. Dinamo keeper Dumitru “Țețe” Moraru (25) was recalled for his first appearance since conceding six against Yugoslavia in a defeat which had scuppered Romania’s chances of making it to the 1978 World Cup. Reigning league champions Dinamo also provided midfielder Ionel Augustin (26). Yet another Corvinul youngster Ioan Andone (21) made a late appearance off the bench, as did Ladislau Bölöni. The 28-year-old midfield linchpin from ASA Târgu Mureș was invited back into the setup after his exclusion from the team, having been considered unreliable, as an ethnic Hungarian, in matches against Hungary. (The Magyars qualified top of the group even without help from their supposed fifth-columnist.)

The experimental line-up managed only a goalless draw in Switzerland, but Lucescu would stick by most of these players for the next few years, and his faith would be rewarded with their loyalty.

The background to this new faith in youth is that, though the senior team had struggled since missing out on the 1972 Euro semi-finals, a new generation of youngsters seemed full of promise. The team they sent to the Youth World Cup, held in Australia in October 1981, achieved third place, with Andone and Rednic in defence and Gabor as player of the tournament up front. Another player, Gheorghe Viscreanu, attempted to defect in Melbourne but eventually ‘chose the freedom not to defect.’ (It turned out that he was given up by the Australian authorities as part of an agreement struck with Ceausescu over the team’s participation in the event.)

Europrep

It was on 1 May 1982, International Workers’ Day, a big event in the socialist calendar, that Euro 1984 qualifying would begin. This was only the second edition of the tournament in which eight teams would contest the final stages, which were to be held in France. Romania had never before qualified for the finals, though they would have done if 1972 had involved eight teams instead of four. At that time, the captain had been none other than Mircea Lucescu, a role he had also fulfilled during the nation’s only post-war appearance at any major tournament, at Mexico 1970.

In the spring of 1982, Romania played two friendlies to prepare for their opening match of the campaign. The first of these, in Brussels, ended in a 4-1 defeat against a strong Belgian team that had finished runners-up to West Germany in the 1980 European championship and had topped their qualifying group for the upcoming World Cup in Spain. The second was the annual neighbourly fixture against Bulgaria, this time played in the town of Ruse, on the south bank of the Danube; the Romanians won 2-1 and took the bragging rights home with them back across the Friendship Bridge.

It won’t surprise you to learn that during this spring Lucescu, still in charge at Corvinul while coaching the national team, brought in two more players from his club, defender Ion Bogdan (26) and midfielder Ioan Petcu (22). He also added a 19-year-old uncapped Steaua attacker called Gabi Balint, who had featured alongside Andone, Gabor and Rednic in the World Youth Cup. The uncapped striker Florea Văetuș (25) was, admittedly, at Dinamo Bucharest, but he’d only just joined them from Corvinul. U Craiova’s 23-year-old centre-forward Rodion Cămătaru was restored to the team after a short absence.

Dinamo pipped defending champions U Craiova to the 1981-82 league title, before wrapping up the double by beating second-division Baia Mare in the cup final in June. The Craiovans had reached the quarter-finals of the European Cup, one of four Eastern bloc teams to do so that season, and were narrowly beaten by eventual runners-up Bayern Munich. No Romanian team had ever got so far in the continent’s premier competition. In the UEFA Cup, having knocked out Inter Milan in the second round, Dinamo were unlucky to meet Sven-Göran Eriksson’s IFK Göteborg, who would go on to win the competition.

Hunedoara, 01.05.1982

The first qualifier would see Cyprus visit – conveniently for Lucescu and many of his squad – the western industrial town of Hunedoara. Looking at the rest of Group 5 – Sweden, Czechoslovakia and Italy – a win here was absolutely vital, especially given that only the top team would qualify for the final tournament. The starting XI to face the Cypriots on 1st May was as follows:

Moraru — Rednic, Ştefănescu, Iorgulescu, Bogdan — Țicleanu, Bölöni, Balaci — Gabor, Cămătaru, Văetuș.

Văetuș and Cămătaru put Romania two goals up in the first quarter, and they saw out the match 3-1 with a second-half goal from Bölöni.

Summer friendlies

The following week, the squad set off for a South American tour, to provide warm-up opposition for Argentina, Peru and Chile, all headed for the World Cup in Spain a month later. An inexperienced starting line-up, averaging only 15 caps apiece, suffered a narrow 1-0 loss in Rosario to the defending world champions, who had rather unfairly added Diego Maradona to their team of Passarella, Kempes, Ardiles, Valdano et al. In Lima, defeat by Peru was all but assured just before half-time when the local referee awarded a soft penalty and promptly sent off both Iorgulescu (the offender) and temporary skipper Balaci (presumably for dissent).

The third match of the tour, played at the infamous national stadium in Pinochet’s Santiago, served as a rude awakening for Chile. The national team had played 50 matches since their last World Cup appearance, in 1974, only two of which had been against national teams from outside South America. Warned by Argentina boss Cesar Luis Menotti about their lack of experience against European teams, Chile found the Romanians formidable representatives of the Old World. Two goals from Klein and a long-range strike from Augustin put the visitors 3-0 up inside the first half-hour, and it is rumoured that during the break officials from the host federation leaned on the Romanians to prevent a national humiliation. Whether or not this is true, Lucescu withdrew Klein, Țicleanu and Ion Geolgău at half-time, and the final score was a very respectable 3-2.

Chile would duly lose all three of their matches at the 1982 edition. After an interesting tour, Lucescu was given the manager’s job on a permanent basis.

Back home in August, Romania welcomed the Japanese national team for two games: a 4-0 win in the northern city of Suceava, and a 3-1 victory in Bucharest. These friendlies saw the return of domestically prolific striker Dudu Georgescu; three goals upped his stats nicely, to leave him level with Iordanescu as Romania’s post-war top scorers.

On 1st September 1982, Denmark were the opponents in another friendly match in Bucharest. The Danes, under Sepp Piontek, were not yet quite the team that would capture hearts later in the decade. They did have the talent, but Simonsen, Lerby, Arnesen and Elkjaer were not in the team for this friendly. Romania won 1-0 courtesy of an early Ilie Balaci strike. UT Arad goalkeeper (and future European Cup hero) Helmut Duckadam made the first of his two international appearances.

Bucharest, 08.09.1982

A week later Sweden visited the Romanian capital for the first proper test of Lucescu’s reign. The Swedes, while not exactly big hitters, had made it to all three of the World Cups during the 1970s, and their top club, IFK Göteborg, had won the UEFA Cup a few months earlier. Thanks to a header by Andone and a bicycle kick by Klein – both from Balaci corners – the Scandinavian visitors were dispatched 2-0. Romania had laid down a marker for the group, and sat out of the action until 4th December, when they would face Italy in Florence. In the meantime, Czechoslovakia drew with Sweden and Italy, and Romania found time to get pumped 4-1 by East Germany in Karl-Marx-Stadt, a match in which UT Arad forward Marcel Coraș made his debut.

Florence, 04.12.1982

So, following the match with Argentina in May, it was the second time this calendar year that Romania had played the reigning world champions, as the Italians had triumphed in Spain in between times. Italy’s line-up featured eight of the team that had started the World Cup final, though Enzo Bearzot’s side had only drawn their opening qualifier at home against Czechoslovakia. For Romania, the major changes were the inclusion of goalkeeper Silviu Lung for his third cap – three years since his second, thanks partly to a severe bout of hepatitis – and of his Craiova team-mate Nicolae Ungureanu at left-back. Both had played for Craiova in the same stadium two months earlier, when they knocked Fiorentina out of the UEFA Cup, as had Ştefănescu, Balaci and Cămătaru.

Fun fact (if true): With six players from Craiova and three from Corvinul, I believe it is the most west-of-Romania-biased national team selection since the late 1920s, when the footballing centre of gravity moved to Bucharest from Timisoara. Anyhoo, here’s the lineup:

Lung — Rednic, Iorgulescu, Ştefănescu (c), Ungureanu — Țicleanu, Bölöni, Balaci, Klein — Gabor, Cămătaru.

Țicleanu was sent off early in the second half, causing Lucescu to remove striker Gabor in favour of defender Andone, but the Italians were unable to score. A goalless draw was most satisfactory for the visitors.

Four days after the Florentine encounter, back home U Craiova overturned a first-leg deficit to knock out a Bordeaux team featuring several of France’s future Euro final winners, including Alain Giresse and Jean Tigana. Țicleanu, Lung, Cămătaru, Ştefănescu, Ungureanu and Balaci all featured in a 2-0 win for the Oltenians, helped by a beautiful strike from Țicleanu and secured with Ion Geolgău’s dramatic extra-time decider.

1983

Further good news came with Cyprus’ two surprise results in the spring of 1983, holding first Italy and then Czechoslovakia to 1-1 draws at home. At Easter 1983, therefore, after three games, Romania had five points, with all their rivals tied on three points and Cyprus behind on two (having played one match extra).

In early 1983 Romania played four friendlies: two against Turkey, one against Greece, and one against Yugoslavia. They would have three crucial qualifiers before the end of the season: at home to Italy and Czechoslovakia in April and May, followed by Sweden away in June. Lucescu introduced only two more debutants into the setup during these friendlies, neither of whom would represent their country again. Beyond this, the coach’s experimentation was restricted to rotating Moraru and Lung between the sticks, and calling on Andone to deputise for Ştefănescu when necessary. Ionel Augustin was given more game time in midfield, while in the forward line the Craiova pair of Geolgău (22) and Sorin Cârțu (27) each got their chance. This article explains that, knowing that Italian coach Enzo Bearzot was scouting at the friendly against Yugoslavia in Timisoara, Lucescu picked an unusual formation for the encounter, with some of the players wearing unfamiliar numbers on their backs. Whether the poor performance against a second-string Yugoslav side was also part of the masterplan is unclear.

Bucharest, 26.04.1983

The team to face Italy was as follows:

Moraru — Rednic, Iorgulescu, Ştefănescu (c), Ungureanu — Augustin, Bölöni, Balaci, Klein — Geolgău, Cămătaru.

Lung was injured and Țicleanu was suspended. For the Italians, Bettega replaced Graziani up front and the central defenders were Scirea and Cabrini; they were otherwise unchanged from the draw in December. Italy, remarkably, had not won a game since the World Cup final nine months earlier and needed a victory to have any chance of qualification. Romania had never beaten Italy in eight attempts.

The 23 August stadium was packed to the rafters with somewhere between sixty and eighty thousand people. The “Great Blond”, Ilie Balaci, was, aged 26, now at the peak of his powers. A regular in the national team since he was 18, Balaci had by now amassed over 60 caps. He had won the Romanian Footballer of the Year award in 1981 and 1982. With his club, U Craiova, he had won three league titles and three cups and, a week earlier, had scored in the semi-final of the UEFA Cup. Against Italy in this match he totally outplayed his marker, the experienced Claudio Gentile, who had kept Maradona in check at the World Cup. In fact, he outplayed everybody.

Balaci’s midfield colleague Bölöni also played a blinder, and beat Dino Zoff after 24 minutes with a thunderous strike from distance – teed up by Balaci, naturally. The goal enabled Romania to sit back and force the Italians to make the play. The visitors were unable to beat Moraru, and Romania had their great win (“Victorie mare! Victorie mare!” as the commentator put it at the final whistle).

Italy had been effectively dumped out of the competition, with three games to go.

Bucharest, 15.05.1983

Next up for Romania was Czechoslovakia. The 1976 European champions and 1980 Olympic gold medallists were a side in decline: they had failed to win a match at the most recent World Cup, and had drawn with Cyprus a few weeks earlier (though they did hammer them 6-0 in Brno a few weeks later). The long-serving likes of Panenka, Masný and Nehoda had all recently retired, and coach Jozef Vengloš had moved to Portugal.

Romania were unchanged, except that Gabor came in for Geolgău and Lung was back between the sticks.

Lung — Rednic, Iorgulescu, Ştefănescu (c), Ungureanu — Augustin, Bölöni, Balaci, Klein — Gabor, Cămătaru.

Ştefănescu gives away a penalty halfway through the first half, bringing down Vizek, who adds a histrionic swallow-dive. Vizek converts the spot-kick himself, and Romania are unable to equalise. It’s a first competitive defeat for Lucescu, and suddenly the group is blown wide open! Romania and Czechoslovakia are level on points at the top, while Sweden have thumped Cyprus and lurk two points behind with a game in hand.

The Swedes do a number on hapless Italy in Gothenburg a fortnight later to draw level, and the Blågult (blue-and-yellow) will be next to host Romania’s yellow-and-blues…

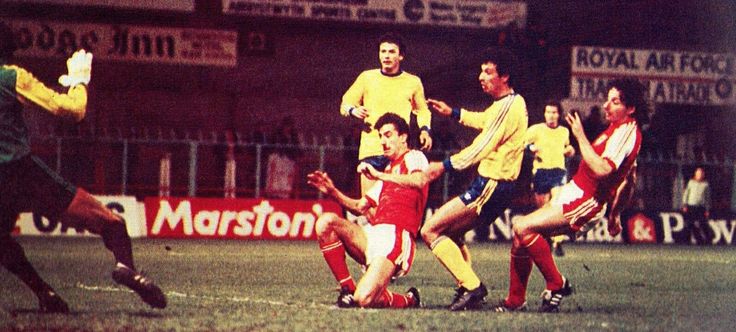

Solna, 09.06.1983

…except that Romania play in all-red on this occasion. It is a more defensive set-up than usual, with Cămătaru the lone striker. Seven Craiova players start. Among them is Balaci, who hasn’t played since injuring his knee in a league match shortly after the Czechoslovakia defeat.

Lung — Rednic, Iorgulescu, Ştefănescu (c), Ungureanu, Andone — Țicleanu, Bölöni, Balaci, Klein — Cămătaru.

Half an hour in, a long diagonal pass from Ştefănescu at the back happens to fall to big Rodion Cămătaru, who hares towards goal before sending an unstoppable low toe-punt past goalkeeper Thomas Ravelli into the net. It’s only the third time he’s scored in his fourteen competitive starts for his country. But it proves the only goal of the game, and that will do very nicely thank you.

Club chat

After countless postponements of league matches due to European commitments, and lengthy international breaks mandated by the federation, the 1982-83 season was finally wrapped up at the beginning of July. U Craiova and Dinamo continued to dominate the domestic scene. The Red Dogs managed to retain their league title – suffering only two defeats all season – ahead of their Craiovan rivals in second place once more. In third place, their highest-ever finish, were Sportul Studenţesc, a small Bucharest club that was about to be gifted a promising teenager, newly arrived from the coast…

Craiova won the Cup, beating Dinamo on penalties in the semi-final and dispatching already-relegated Poli Timişoara in the final a week later with two goals from Cămătaru. However, because entries for the European Cup-Winners’ Cup had closed in June, Universitatea were denied the chance to compete in the slightly more prestigious and very winnable competition. They had to settle for the UEFA Cup again, unseeded, at the expense of Argeș who were packed off to the inconsequential Balkan Cup. The head of the federation was forced to resign.

This administrative cock-up was all the more galling as U had performed admirably on the European stage for the past three seasons. Their Big Cup quarter-final in 1982 was surpassed the following year, as ‘Craiova Maxima’ reached the semi-final of the UEFA Cup. After Fiorentina, Shamrock Rovers and Bordeaux, Kaiserlautern were the next to fall, and Benfica only squeaked into the final on away goals after both legs of the semi were drawn. Benfica’s coach? Sven-Göran Eriksson. (Read about Craiova’s highly unusual trip to Lisbon here.)

Four games into the 1983-84 season, controversy hit as league leaders Sportul faced U Craiova. With the score tied at 1-1 the Craiovans, in protest at a hotly disputed 85th-minute penalty, awarded to Hagi and scored by Coraș, walked off the field and straight onto the team bus. The match was subsequently awarded 3-0 to the home side. Silviu Lung, ringleader of the protest, was handed a three-match ban for unsportsmanlike behaviour; several other players got off with two-match bans. Conveniently, especially since Ungureanu was one of the latter group, the authorities decreed that the bans would be enforced only after the national team had completed their qualifiers. A strong message on sportsmanship there.

The King is coming

As Romania’s next qualifier was not until November, friendlies were played. The first of these, a goalless draw against Norway in Oslo, is interesting for one reason only: it was the international debut of 18-year-old Gheorghe Hagi. The youngster had played one full season in the top flight with his hometown club Constanța and, in spite of his team’s relegation, had impressed enough to be courted by Dinamo, Steaua and U Craiova. Yet it was Sportul Studențesc who ended up with him.

Next came a match against East Germany, the day after socialist Romania’s great national holiday, 23 August. The day celebrated the great national anti-fascist insurrection in summer 1944, when the Nazi yoke and the Antonescu dictatorship were thrown off, supposedly by a popular uprising. The truth, as understood these days, is somewhat different from the official Party line that still prevailed in 1983. Communist propaganda couldn’t admit that in fact it happened through a royal coup. Anyway, 23 August was a huge occasion and the team were required to march past Ceausescu as part of the capital’s big parade. Romania beat the GDR 1-0.

Friendlies against Poland, Wales and Israel follow. Hagi, his free-scoring new Sportul team-mate Marcel Coraș, and Steaua defender Ştefan Iovan (23), start to get more game time. Balaci plays only ten minutes across these friendly games, presumably (still/again) injured. Wales, impressively, spank a full-strength Romania team 5-0 in Wrexham in October: not the ideal preparation for anything. And then a draw with Israel completes an underwhelming sequence of matches for the Romanians.

Meanwhile, both the country’s representatives in the UEFA Cup went out in the first round: Craiova to Hajduk Split – being unseeded had landed them with a tough draw – and Sportul to Sturm Graz. Only Dinamo Bucharest remained to fly the flag, which they were doing admirably. The 23 August Stadium witnessed a 3-0 thrashing of defending champions Hamburg in October; a quarter-final against Soviet champions Dinamo Minsk awaited in March.

Back on task

While the Romanians were sitting on their hands and arguing about penalties, Sweden were busy winning at home to Czechoslovakia and, remarkably, hammering Italy 3-0 in Naples. The Swedes now sat top of the group by two points, their fixtures completed. Because of their inferior goal difference, to be sure of qualifying, Romania needed a win and a draw from their remaining two matches, both away, against Cyprus and Czechoslovakia. On 12 November in Limassol the Cypriots held out well until Bölöni’s header broke their resistance in the 78th minute. A 1-0 win, while not ideal, was just about enough for the Romanians going into the last fixture, despite a victory for the Slovakoczechs over Italy a few days later in Prague.

Bratislava, 30.11.1983

So the stage is set. Romania need a draw to qualify; the Czechoslovaks need to win. Star player Balaci is still out, so the team reads:

Lung — Negrila, Ştefănescu (c), Iorgulescu, Ungureanu, Rednic — Klein, Bölöni, Geolgău, Gabor — Cămătaru.

On a total mudbath of a pitch, the hosts have two goals correctly ruled out, for handball and offside, and it takes until the 65th minute for the deadlock to be broken. It’s that man Ion Geolgău who gets the goal, a powerful shot from the edge of the area that the keeper should have got a hand to. Luhovy’s late equaliser cannot quite spoil the party, as Romania hold on to secure their first ever European Championship finals spot!

Ion Geolgău, previously known as “Gheorghiță”, now acquired a new nickname: the Hero of Bratislava. Popular poet Adrian Paunescu would pen a verse in honour of this great night: “From Pielești to Bratislava / From Craiova to Glasgow / Europe hums / Come on Geolgău, Geolgău, Geolgău!”

Leave a comment