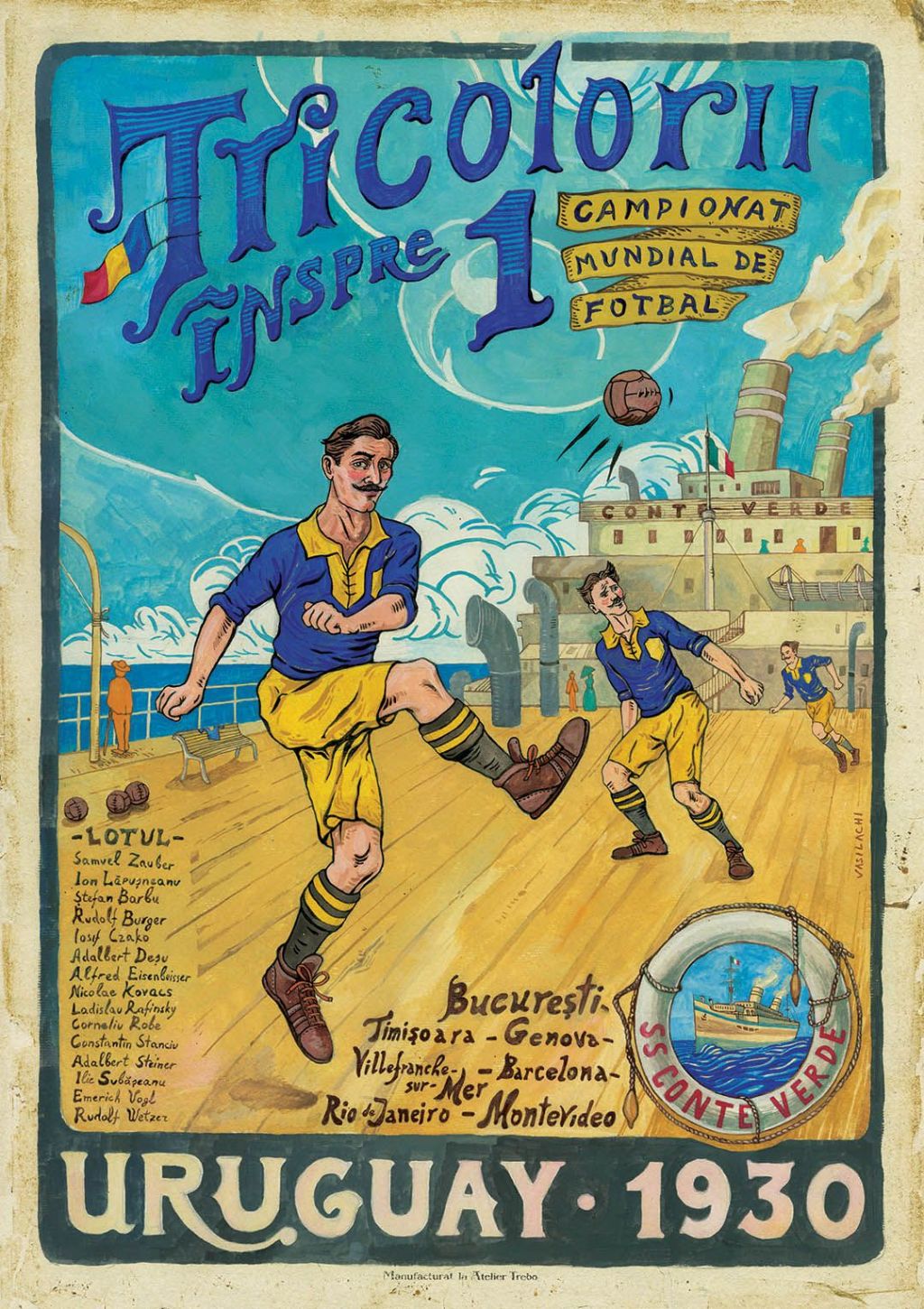

Only about 188 weeks to go until the long-awaited Qatar World Cup kicks off!!!! That, and the upcoming 88.75th anniversary of the event in question, combine to mean it must be another timely Romaniaballs blog post. We will be EXPLODING myths, EXPOSING biased reporting and possibly even EXPANDING our knowledge of men in big, baggy shorts running around in black and white.

In the lead-up to every World Cup finals, articles are written about the very first tournament, held in Uruguay in July 1930. The story about Romania’s participation, published on FIFA’s own website in 2013 and written in the site’s house style of “primary-school guided reading book”, is peppered not only with very short sentences. And exclamation marks! It also repeats the supposedly well-known “facts” that: (1) King Carol II secured Romania’s place at the inaugural World Cup; (2) he picked the squad; and (3) he oversaw training on board the ship the team took to Montevideo.

Mostly cobblers. But then, august and estimable outlets have published similar claims, tucked away in otherwise sound articles. I am too trusting of online sources. The story below is (probably) closer to the truth, although I don’t pretend to have all the answers and I still have plenty of questions. And I really don’t think the story loses too much romance by edging out the monarch: there are other fascinating characters we ought to celebrate, from an age when the sport was emerging from amateurism. In Romanian, the primary sources are the diary kept by Romania captain Rudy Wetzer, published by the renowned journalist Ioan Chirilă in the 1960s, and despatches sent home to Bucharest by the one pressman on the trip, a certain Moritz Beilis. We might call upon the memories of other participants too. Full disclosure: I haven’t actually read Chirilă’s book as my Romanian isn’t good enough: I’ve relied on excerpts used in various articles (see part 2 for the sources I did use).

Getting started

In order to compete in Uruguay, a country had to have a football association that was a member of FIFA. The Romanian Football Federation (FRFA) was thus formed in February 1930. Its founding secretary was a 29-year-old lawyer named Octav Luchide, who had, as a schoolboy, been a founder member of the Sportul Studențesc club in Bucharest; he went on to play for Sportul’s rugby team in a period of domestic domination in the 1920s. He had also written books on philately, and translated libretti in his post as secretary of the national opera. Welcome to the inter-war years!

It is often reported that the newly installed King Carol II – a hedonistic playboy and therefore, naturally, a football enthusiast – insisted that his country send a team to compete, but I don’t know where this idea originates. He only returned from exile on 6 June 1930 and it is hard to imagine football being the number one national priority for his reign. Indeed, the very idea that Carol was a football fan appears to be conjecture: in a magazine interview in the early twenties, the monarch listed his favourite sports as tennis, motor racing and winter sports. Wetzer’s journal tells us that discussions about entering the World Cup were well underway in March, and that the driving force was Luchide, nicknamed “the Greek”. By April, Wetzer knew that he would not only be playing but also selecting the team to travel. Here is an excerpt:

’18 March. Rumour has it that our national team will this summer leave for Montevideo, in Uruguay, for the first World Championship of football. Is it possible? I bet it’s just talk. I don’t believe it.

23 March. Unbelievable. I’ve heard that Uruguay is paying all the expenses. I absolutely have to find Luchide.

26 March. I still don’t believe it. I spread the world map out on the table and put a ruler between Bucharest and Montevideo. It’s about 3,000 kilometres to Gibraltar. And then, on the ocean, roughly another 8,000. And that’s in two straight lines. I didn’t stretch around the bulge of Africa. I still don’t believe.

10 April. “Mercure”, eight in the evening. I suddenly got my good mood back. At a table is Costel Rădulescu, cheerful as always and telling jokes.

- “Greetings, Rudi!”

- “Hello Costel!”

- “Congratulations, old man!”

- “?!”

- “You’re one of the fifteen Romanian footballers who will discover for the first time how the ball bounces on the turf in the southern hemisphere.”

- “Quit joking.”

- “It’s all arranged. When the Greek wants something, he makes it happen.”

- “And the money?”

- “We haven’t a groat. But South America is paying down to the last centime, because we honour them with our presence. Don’t forget, Rudi, we are the first country signed up for the Jules Rimet Cup. Take it from me, this Jules Rimet is a genius, and this Cup of his is going to last until the Earth freezes.”’

The trophy would not bear Rimet’s name until 1946, but let us indulge Wetzer or his editor Chirilă for what I assume is the creative use of hindsight.

This Wetzer was no ingénue. He was 29 years old, had played for big clubs in Yugoslavia and Hungary, and had won the Romanian title twice as a forward for the all-conquering Chinezul team from his home town Timișoara. But, like most of his contemporaries around the world, his football had been exclusively a regional pursuit. He had featured in twelve of the 22 international matches that Romania had contested up to that point, but – with the exception of a disastrous 1924 Olympics in Paris – these had taken him no further than Istanbul or Vienna. The idea of travelling to the other side of the world clearly enraptured him.

Luchide appointed Wetzer in the role of trainer, responsible for the selection of players, while Costel Rădulescu, an experienced coach and referee, would function as manager. Chinezul Timișoara, the team which had dominated Romanian football throughout the 1920s, winning six consecutive national titles, had recently fallen apart due to financial problems, corruption and infighting, and many of the best players were now at clubs in the capital. Asked by Luchide how he saw the Romanian team in Montevideo, Wetzer replied, “If Chinezul were Chinezul, I’d have answered straight away. However, I think the best solution is a Bucharest-Timișoara combination. If, of course, we solve the problem of releasing the players.”

Many European nations were umming and ahhing over participation, whether because of financial constraints (it was the Depression, after all) or because of the length of time clubs would have to do without their best players, since it would take several weeks to get to Uruguay and back. To encourage participation, Uruguay offered to pay the cost of the competitors’ travel and board: the country was celebrating the centenary of its independence and the bigger the tournament the better.

Eventually, all of the major powers of continental football – Italy, Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia (let’s not even bother to mention the isolationist British) – chose to stay at home. This would be no bad thing for the Romanians, as it would attract all the more attention to them as one of only four European teams to compete, alongside France, Belgium and Yugoslavia.

Legend has it that at this juncture the king got involved and made threats, to secure the players’ release and extract a promise that they could have their jobs back on their return. This is plausible: Luchide was rumoured to have had some connection to the royal palace. I’m not sure if Brunelli, who also owned the Italian-Romanian Commercial Bank, would have appreciated (or been cowed by) this kind of approach, but who knows? In any case, the problem was resolved and the pair were granted leave. Unpaid, naturally.

The squad

If you’re counting – and a lot of people were, in a somewhat anxious, newly-expanded country with a large ethnic-minority population – my back-of-the-envelope totting-up gives us four Germans, three Hungarians, two Jews and six ethnic Romanians. No fewer than nine of the fifteen were natives of the Banat, the western region – part of Hungary until 1920 – which had dominated Romanian football throughout the decade. Only three, meanwhile, had been born within the borders of pre-war Romania. Yet the recent shift in power and wealth to the national capital was demonstrated by the fact that only three of the squad were contracted to Timisoara clubs, while eight were at clubs in Bucharest.

Forward Nicolae Covaci came from Banatul Timișoara, while city rivals Chinezul supplied defenders Rudolf Bürger and Adalbert Steiner. UD Reșița, also from the Banat, supplied defender Iosif Czako and forward Adalbert Deșu, and from Gloria of nearby Arad came skilful attacker Ștefan Barbu. Besides Raffinsky, Vogl and Wetzer from Juventus, Bucharest teams were represented by Venus forward Constantin Stanciu; first-choice goalie Jean Lăpușneanu of Sportul Studențesc; his backup Samuel Zauber from Maccabi; and, from Olimpia, halfback Corneliu Robe and yet another forward, Ilie Subășeanu. Many of the players were known by slightly different names during their careers, especially if they had played abroad or were of ethnic minority origin. For example, Nicolae Covaci was called Miklós Kovács in his native Hungarian. Czako’s name was sometimes Romanianised as Țaco, so he would have formed a very tasty back-line alongside Bürger. Yum. Taking this flexi-naming to the extreme, from Dragoș Vodă Cernăuți in northern Bucovina came centre half, dead-ball specialist and figure skater Alfred Eisenbeisser, who was also known as Fredi Fieraru.

Departure

Departure

On the morning of 16 June 1930, ten days after the Juventus team had secured its first national title by beating Gloria Arad, the delegation gathered on the platform at Bucharest’s Gara de Nord, ready to board the 8.05 train to Trieste. Family and friends were present to say goodbye to loved ones whom they would not see for several weeks. The football federation treasurer, Nicu Lucescu, hadn’t slept for five days and was anxiously counting the party like a parent.

That evening, the delegation disembarked at Timișoara, where they were to collect the remaining members of the party: eight Banat-based players, and the manager Rădulescu, had travelled home a day or two earlier to spend time with their families. After a break of a few hours, the whole gang was ready to head for the Italian port of Genoa. They were travelling second class, on Luchide’s initiative, and with the money saved had bought a set of matching suits in Bucharest so that they would look like a team. As Wetzer put it: “Clothes do not make a man, but a football team in fine suits is a true team.” But second class meant wooden benches, no beds, and the discomfort was not ideal for a group of elite athletes.

The train journey lasted two nights, and musical diversion began early. An a cappella choir was formed under the guidance of Subășeanu, a keen pianist. At the Yugoslav border with Italy, tired of the banter of the bucureștenii, Wetzer went to look out of the window. As the train approached a station, he mistook an olive-oil advert for the station name and announced loudly to all his companions that they had reached their first Italian town, “Olio Sasso”. When they finally got off the train at Genoa, Wetzer recalled,

‘I said to Costel Rădulescu that I’d been thinking all night and that our attack was too lightweight. He was annoyed: “My dear Rudy, this kind of thought would have been good at the ‘Mercure’, over a cup of coffee. Now is no time for regrets.” ‘

Banatul Timișoara’s twenty-year-old hot-shot Ștefan Dobay, who had scored on his debut against Greece in May, had been cut from the squad. Unhampered by this early disappointment, he would go on to have a truly glittering career with Ripensia and Romania throughout the 1930s.

Genoa and the Conte Verde

The party is greeted at the station by the consul and his wife, a group of Romanian students, and the former boss of Juventus București. The Romanian community of Genoa stands them dinner at a hotel. The wine flows, and the players’ choir is in good voice, giving an impressive rendition of ‘Giovinezza’, the national anthem of Fascist Italy, to the delight of the Italians. Afterwards they stagger down to the harbour to see the ship they will be boarding the next day. There she is, the gigantic, Clyde-built transatlantic liner Conte Verde.

On 21 June, at eleven a.m., the Romanians board the vessel. Equipped with ballroom, library, swimming pool and gym, it is a floating luxury hotel. The team are in four-berth cabins. As the anchor is raised and the huge boat begins to move, the players look toward the shore: a crowd has gathered to bid them farewell. The choir sings ‘Giovinezza’ again, which endears them to the mostly Italian passengers, but then the mood turns melancholy as the Romanians contemplate their long journey into the unknown. Some of them have never even seen the sea before. An opulent lunch is served, and then at 4pm the ship arrives at Villefranche on the French Riviera to pick up more passengers. Rădulescu reminds his charges that they are ambassadors for their country: they are to keep their elbows at their sides when eating, and ought not to neglect the toothpick.

Part 2 to follow…

![carol ii from Fun-loving Carol II [madmonarchist.blogspot.com]](https://romaniaballs.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/carol-ii-from.jpg?w=250&resize=250%2C328&h=328#038;h=328)

![wetzer from druckeria Rudy Wetzer [druckeria.ro]](https://romaniaballs.files.wordpress.com/2019/04/wetzer-from-druckeria.jpg?w=242&resize=242%2C328&h=328#038;h=328)

Leave a comment